This blog has moved.

New blog is here: https://1f6042.blogspot.com/

[If the formatting in this blog post looks wrong, you can try the version on my website https://1f604.com/liburing_b3sum/article.html or this version on Code Project https://www.codeproject.com/Articles/5365529/Fastest-b3sum-using-io-uring-faster-than-cat-to-de]

I wrote two versions of a program which computes the BLAKE3 hash of a file (source code here), a single-threaded version in C and a multi-threaded version in C++, both of which use io_uring. The single-threaded version is around 25% faster than the official Rust b3sum on my system and is slightly faster than cat to /dev/null on my system, and is also slightly faster than fio on my system, which I used to measure the sequential read speed of a system (see Additional Notes for the parameters that I used passed to fio and other details). The single-threaded version is able to hash a 10GiB file in 2.899s, which works out to around 3533MiB/s, which is roughly the same as the read speed advertised for my NVME drive (“3500MB/s”), which leads me to believe that it is the fastest possible file hashing program on my system and cannot be any faster because a file hashing program cannot finish hashing a file before it has finished reading the last block of the file from the disk. My multi-threaded implementation is around 1% slower than my single-threaded implementation.

I provide informal proofs that both versions of my program are correct (i.e. will always return the correct result) and will never get stuck (i.e. will eventually finish). The informal proofs are provided along with an explanation of the code in the The Code Explained section of this article.

My program is extremely simple, generic, and can be easily modified to do what you want, as long as what you want is to read from a file a few blocks at a time and process these blocks while waiting for the next blocks to arrive - I think this is an extremely common use case, so I made sure that it is trivially easy to adapt my program for your needs - if you want to do something different with each block of the file, all you need to do is to replace the call to the hashing function with a call to your own data processing function.

For these tests, I used the same 1 GiB (or 10 GiB) input file and

always flushed the page cache before each test, thus ensuring that the

programs are always reading from disk. Each command was run 10 times and

I used the “real” result from time to calculate the

statistics. I ran these commands on a Debian 12 system (uname -r returns

“6.1.0-9-amd64”) using ext4 without disk encryption and without LVM.

| Command | Min | Median | Max |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --num-threads 1 | 0.404s | 0.4105s | 0.416s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --num-threads 2 | 0.474s | 0.4755s | 0.481s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --num-threads 3 | 0.44s | 0.4415s | 0.451s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --num-threads 4 | 0.443s | 0.4475s | 0.452s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --num-threads 5 | 0.454s | 0.4585s | 0.462s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --num-threads 6 | 0.456s | 0.4605s | 0.463s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --num-threads 7 | 0.461s | 0.4635s | 0.468s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --num-threads 8 | 0.461s | 0.464s | 0.47s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time b3sum 1GB.txt --no-mmap | 0.381s | 0.386s | 0.394s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time ./b3sum_linux 1GB.txt --no-mmap | 0.379s | 0.39s | 0.404s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time cat 1GB.txt | ./example | 0.364s | 0.3745s | 0.381s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time cat 1GB.txt > /dev/null | 0.302s | 0.302s | 0.303s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time dd if=1GB.txt bs=64K | ./example | 0.338s | 0.341s | 0.348s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time dd if=1GB.txt bs=64K of=/dev/null | 0.303s | 0.306s | 0.308s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time dd if=1GB.txt bs=2M | ./example | 0.538s | 0.5415s | 0.544s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time dd if=1GB.txt bs=2M of=/dev/null | 0.302s | 0.303s | 0.304s |

| fio --name TEST --eta-newline=5s --filename=temp.file --rw=read --size=2g --io_size=1g --blocksize=512k --ioengine=io_uring --fsync=10000 --iodepth=2 --direct=1 --numjobs=1 --runtime=60 --group_reporting | 0.302s | 0.3025s | 0.303s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time ./liburing_b3sum_singlethread 1GB.txt 512 2 1 0 2 0 0 | 0.301s | 0.301s | 0.302s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time ./liburing_b3sum_multithread 1GB.txt 512 2 1 0 2 0 0 | 0.303s | 0.304s | 0.305s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time ./liburing_b3sum_singlethread 1GB.txt 128 20 0 0 8 0 0 | 0.375s | 0.378s | 0.384s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time ./liburing_b3sum_multithread 1GB.txt 128 20 0 0 8 0 0 | 0.304s | 0.305s | 0.307s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time xxhsum 1GB.txt | 0.318s | 0.3205s | 0.325s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time cat 10GB.txt > /dev/null | 2.903s | 2.904s | 2.908s |

| echo 1 > /proc/sys/vm/drop_caches; sleep 1; time ./liburing_b3sum_singlethread 10GB.txt 512 4 1 0 4 0 0 | 2.898s | 2.899s | 2.903s |

In the table above, liburing_b3sum_singlethread and liburing_b3sum_multithread are my own io_uring-based implementations of b3sum (more details below), and I verified that my b3sum implementations always produced the same BLAKE3 hash output as the official b3sum implementation. The 1GB.txt file was generated using this command:

dd if=/dev/urandom of=1GB.txt bs=1G count=1

I installed b3sum using this command:

cargo install b3sum

$ b3sum --version b3sum 1.4.1

I downloaded the b3sum_linux program from the BLAKE3 Github Releases page (it was the latest Linux binary):

$ ./b3sum_linux --version b3sum 1.4.1

I compiled the example program from the example.c file in the BLAKE3 C repository as per the instructions in the BLAKE3 C repository:

gcc -O3 -o example example.c blake3.c blake3_dispatch.c blake3_portable.c \ blake3_sse2_x86-64_unix.S blake3_sse41_x86-64_unix.S blake3_avx2_x86-64_unix.S \ blake3_avx512_x86-64_unix.S

I installed xxhsum using this command:

apt install xxhash

$ xxhsum --version

xxhsum 0.8.1 by Yann Collet

compiled as 64-bit x86_64 autoVec little endian with GCC 11.2.0`

As you can see from the results above, my single-threaded implementation is slightly faster than my multi-threaded implementation.

If the single-threaded version is faster, then why did I mention the

multi-threaded version? Because, as the table above shows, the

single-threaded version needs O_DIRECT in order to be fast (the flag that controls whether or not to use O_DIRECT is the third number after the filename in the command line arguments). The multi-threaded version is fast even without O_DIRECT (as the table shows, the multi-threaded version will hash a 1GiB file in 0.304s with O_DIRECT and 0.305s without O_DIRECT). Why would anyone care about whether or not a program uses O_DIRECT? Because the O_DIRECT

version will not put the file into the page cache (it doesn’t evict the

file from the page cache either - it just bypasses the page cache

altogether). This is good for the use case where you just want to

process (e.g. hash) a large number of large files as fast as possible,

accessing each file exactly once each, for example if you want to

generate a list of hashes of every file on your system. It is not so

good for the use case where you have only one file and you want to hash

it with this program and then another program (e.g. xxhsum) immediately

afterwards. That’s why I mentioned the multi-threaded version of my

program - it is fast even when not using O_DIRECT, unlike the single-threaded version.

One major caveat is that my program currently uses the C version of the BLAKE3 library. BLAKE3 has two versions - a Rust version and a C version, and only the Rust version supports multithreading - the C version currently does not support multithreading:

Unlike the Rust implementation, the C implementation doesn’t currently support multithreading. A future version of this library could add support by taking an optional dependency on OpenMP or similar. Alternatively, we could expose a lower-level API to allow callers to implement concurrency themselves. The former would be more convenient and less error-prone, but the latter would give callers the maximum possible amount of control. The best choice here depends on the specific use case, so if you have a use case for multithreaded hashing in C, please file a GitHub issue and let us know.

Multithreading could be beneficial when your IO speed is faster than your single-core hashing speed. For example, if you have a fast NVME, for example let’s say your NVME can do 7GB/s read but your CPU can only compute a BLAKE3 hash at say 4GB/s on a single core, then you might benefit from multithreading which enables you to have multiple CPU cores hashing the file at the same time. So the most obvious next step would be add io_uring support to the Rust b3sum implementation so that Linux systems can benefit from the faster IO. An alternative would be to add multithreading support to the C BLAKE3 implementation.

(Actually, having said that, I’m not sure if multithreading would always be faster. On most storage devices, sequential read is significantly faster than random read, and it looks like the current multithreaded Rust implementation does reads all over the file rather than reading the file in sequentially. So I think it’s possible that, in some situations, doing random reads might slow down IO so much that it will actually be slower than just sequentially reading in the file and doing hashing on a single core. But, obviously this depends on the hardware that you have. The ideal would be multi-core hashing with sequential read, but I’m not sure if the BLAKE3 algorithm actually allows that. If not, I guess you could just hash each chunk of the file separately, obtaining a list of hashes, then you could just store that list or you could store a hash of that list if you want to save space. That actually was my original plan before I discovered that BLAKE3 on a single core was faster than file read on my system.)

So yeah, I’m pretty sure my program runs at the theoretical speed limit of my system i.e. it is literally the fastest possible file hashing program on my system i.e. there is no further room for optimization - this one fact pleased me more than anything else. I wrote this article because I wanted to do a writeup explaining my program, and how I got my program to this point and actually I think it’s pretty surprising that nobody else (as far as I know) has used io_uring for a file hashing program yet - it’s such a perfect use case for io_uring, it’s pretty much the lowest-hanging fruit that I can think of.

Another caveat is that io_uring is Linux only, so this program cannot run on other operating systems.

I will first explain the single-threaded version then explain the multi-threaded version.

So, here is the single-threaded version:

/* SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT */

/*

* Compile with: gcc -Wall -O3 -D_GNU_SOURCE liburing_b3sum_singlethread.c -luring libblake3.a -o liburing_b3sum_singlethread

* For an explanation of how this code works, see my article/blog post: https://1f604.com/b3sum

*

* This program is a modified version of the liburing cp program from Shuveb Hussain's io_uring tutorial.

* Original source code here: https://github.com/axboe/liburing/blob/master/examples/io_uring-cp.c

* The modifications were made by 1f604.

*

* The official io_uring documentation can be seen here:

* - https://kernel.dk/io_uring.pdf

* - https://kernel-recipes.org/en/2022/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/axboe-kr2022-1.pdf

*

* Acronyms: SQ = submission queue, SQE = submission queue entry, CQ = completion queue, CQE = completion queue event

*/

#include "blake3.h"

#include "liburing.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <assert.h>

#include <sys/ioctl.h>

/* Constants */

static const int ALIGNMENT = 4 * 1024; // Needed only because O_DIRECT requires aligned memory

/* ===============================================

* ========== Start of global variables ==========

* ===============================================

* Declared static because they are only supposed to be visible within this .c file.

*

* --- Command line options ---

* The following variables are set by the user from the command line.

*/

static int g_queuedepth; /* This variable is not really the queue depth, but is more accurately described as

* "the limit on the number of incomplete requests". Allow me to explain.

* io_uring allows you to have more requests in-flight than the size of your submission

* (and completion) queues. How is this possible? Well, when you call io_uring_submit,

* normally it will submit ALL of the requests in the submission queue, which means that

* when the call returns, your submission queue is now empty, even though the requests

* are still "in-flight" and haven't been completed yet!

* In earlier kernels, you could overflow the completion queue because of this.

* Thus it says in the official io_uring documentation (https://kernel.dk/io_uring.pdf):

* Since the sqe lifetime is only that of the actual submission of it, it's possible

* for the application to drive a higher pending request count than the SQ ring size

* would indicate. The application must take care not to do so, or it could risk

* overflowing the CQ ring.

* That is to say, the official documentation recommended that applications should ensure

* that the number of in-flight requests does not exceed the size of the submission queue.

* This g_queuedepth variable is therefore a limit on the total number of "incomplete"

* requests, which is the number of requests on the submission queue plus the number of

* requests that are still "in flight".

* See num_unfinished_requests for details on how this is implemented. */

static int g_use_o_direct; // whether to use O_DIRECT

static int g_process_in_inner_loop; // whether to process the data inside the inner loop

static int g_use_iosqe_io_drain; // whether to issue requests with the IOSQE_IO_DRAIN flag

static int g_use_iosqe_io_link; // whether to issue requests with the IOSQE_IO_LINK flag

//static int g_use_ioring_setup_iopoll; // when I enable IORING_SETUP_IOPOLL, on my current system,

// it turns my process into an unkillable zombie that uses 100% CPU that never terminates.

// when I was using encrypted LVM, it just gave me error: Operation not supported.

// I decided to not allow users to enable that option because I didn't want them

// to accidentally launch an unkillable never-ending zombie process that uses 100% CPU.

// I observed this behavior in fio too when I enabled --hipri on fio, it also turned into

// an unkillable never-ending zombie process that uses 100% CPU.

static size_t g_blocksize; // This is the size of each buffer in the ringbuf, in bytes.

// It is also the size of each read from the file.

static size_t g_numbufs; // This is the number of buffers in the ringbuf.

/* --- Non-command line argument global variables --- */

blake3_hasher g_hasher;

static int g_filedescriptor; // This is the file descriptor of the file we're hashing.

static size_t g_filesize; // This will be filled in by the function that gets the file size.

static size_t g_num_blocks_in_file; // The number of blocks in the file, where each block is g_blocksize bytes.

// This will be calculated by a ceiling division of filesize by blocksize.

static size_t g_size_of_last_block; // The size of the last block in the file. See calculate_numblocks_and_size_of_last_block.

static int producer_head = 0; // Position of the "producer head". see explanation in my article/blog post

static int consumer_head = 0; // Position of the "consumer head". see explanation in my article/blog post

enum ItemState { // describes the state of a cell in the ring buffer array ringbuf, see my article/blog post for detailed explanation

AVAILABLE_FOR_CONSUMPTION, // consumption and processing in the context of this program refers to hashing

ALREADY_CONSUMED,

REQUESTED_BUT_NOT_YET_COMPLETED,

};

struct my_custom_data { // This is the user_data associated with read requests, which are placed on the submission ring.

// In applications using io_uring, the user_data struct is generally used to identify which request a

// completion is for. In the context of this program, this structure is used both to identify which

// block of the file the read syscall had just read, as well as for the producer and consumer to

// communicate with each other, since it holds the cell state.

// This can be thought of as a "cell" in the ring buffer, since it holds the state of the cell as well

// as a pointer to the data (i.e. a block read from the file) that is "in" the cell.

// Note that according to the official io_uring documentation, the user_data struct only needs to be

// valid until the submit is done, not until completion. Basically, when you submit, the kernel makes

// a copy of user_data and returns it to you with the CQE (completion queue entry).

unsigned char* buf_addr; // Pointer to the buffer where the read syscall is to place the bytes from the file into.

size_t nbytes_expected; // The number of bytes we expect the read syscall to return. This can be smaller than the size of the buffer

// because the last block of the file can be smaller than the other blocks.

//size_t nbytes_to_request; // The number of bytes to request. This is always g_blocksize. I made this decision because O_DIRECT requires

// nbytes to be a multiple of filesystem block size, and it's simpler to always just request g_blocksize.

off_t offset_of_block_in_file; // The offset of the block in the file that we want the read syscall to place into the memory location

// pointed to by buf_addr.

enum ItemState state; // Describes whether the item is available to be hashed, already hashed, or requested but not yet available for hashing.

int ringbuf_index; // The slot in g_ringbuf where this "cell" belongs.

// I added this because once we submit a request on submission queue, we lose track of it.

// When we get back a completion, we need an identifier to know which request the completion is for.

// Alternatively, we could use something to map the buf_addr to the ringbuf_index, but this is just simpler.

};

struct my_custom_data* g_ringbuf; // This is a pointer to an array of my_custom_data structs. These my_custom_data structs can be thought of as the

// "cells" in the ring buffer (each struct contains the cell state), thus the array that this points to can be

// thought of as the "ring buffer" referred to in my article/blog post, so read that to understand how this is used.

// See the allocate_ringbuf function for details on how and where the memory for the ring buffer is allocated.

/* ===============================================

* =========== End of global variables ===========

* ===============================================*/

static int setup_io_uring_context(unsigned entries, struct io_uring *ring)

{

int rc;

int flags = 0;

rc = io_uring_queue_init(entries, ring, flags);

if (rc < 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "queue_init: %s\n", strerror(-rc));

return -1;

}

return 0;

}

static int get_file_size(int fd, size_t *size)

{

struct stat st;

if (fstat(fd, &st) < 0)

return -1;

if (S_ISREG(st.st_mode)) {

*size = st.st_size;

return 0;

} else if (S_ISBLK(st.st_mode)) {

unsigned long long bytes;

if (ioctl(fd, BLKGETSIZE64, &bytes) != 0)

return -1;

*size = bytes;

return 0;

}

return -1;

}

static void add_read_request_to_submission_queue(struct io_uring *ring, size_t expected_return_size, off_t fileoffset_to_request)

{

assert(fileoffset_to_request % g_blocksize == 0);

int block_number = fileoffset_to_request / g_blocksize; // the number of the block in the file

/* We do a modulo to map the file block number to the index in the ringbuf

e.g. if ring buf_addr has 4 slots, then

file block 0 -> ringbuf index 0

file block 1 -> ringbuf index 1

file block 2 -> ringbuf index 2

file block 3 -> ringbuf index 3

file block 4 -> ringbuf index 0

file block 5 -> ringbuf index 1

file block 6 -> ringbuf index 2

And so on.

*/

int ringbuf_idx = block_number % g_numbufs;

struct my_custom_data* my_data = &g_ringbuf[ringbuf_idx];

assert(my_data->ringbuf_index == ringbuf_idx); // The ringbuf_index of a my_custom_data struct should never change.

my_data->offset_of_block_in_file = fileoffset_to_request;

assert (my_data->buf_addr); // We don't need to change my_data->buf_addr since we set it to point into the backing buffer at the start of the program.

my_data->nbytes_expected = expected_return_size;

my_data->state = REQUESTED_BUT_NOT_YET_COMPLETED; /* At this point:

* 1. The producer is about to send it off in a request.

* 2. The consumer shouldn't be trying to read this buffer at this point.

* So it is okay to set the state to this here.

*/

struct io_uring_sqe* sqe = io_uring_get_sqe(ring);

if (!sqe) {

puts("ERROR: FAILED TO GET SQE");

exit(1);

}

io_uring_prep_read(sqe, g_filedescriptor, my_data->buf_addr, g_blocksize, fileoffset_to_request);

// io_uring_prep_read sets sqe->flags to 0, so we need to set the flags AFTER calling it.

if (g_use_iosqe_io_drain)

sqe->flags |= IOSQE_IO_DRAIN;

if (g_use_iosqe_io_link)

sqe->flags |= IOSQE_IO_LINK;

io_uring_sqe_set_data(sqe, my_data);

}

static void increment_buffer_index(int* head) // moves the producer or consumer head forward by one position

{

*head = (*head + 1) % g_numbufs; // wrap around when we reach the end of the ringbuf.

}

static void resume_consumer() // Conceptually, this resumes the consumer "thread".

{ // As this program is single-threaded, we can think of it as cooperative multitasking.

while (g_ringbuf[consumer_head].state == AVAILABLE_FOR_CONSUMPTION){

// Consume the item.

// The producer has already checked that nbytes_expected is the same as the amount of bytes actually returned.

// If the read syscall returned something different to nbytes_expected then the program would have terminated with an error message.

// Therefore it is okay to assume here that nbytes_expected is the same as the amount of actual data in the buffer.

blake3_hasher_update(&g_hasher, g_ringbuf[consumer_head].buf_addr, g_ringbuf[consumer_head].nbytes_expected);

// We have finished consuming the item, so mark it as consumed and move the consumer head to point to the next cell in the ringbuffer.

g_ringbuf[consumer_head].state = ALREADY_CONSUMED;

increment_buffer_index(&consumer_head);

}

}

static void producer_thread()

{

int rc;

unsigned long num_blocks_left_to_request = g_num_blocks_in_file;

unsigned long num_blocks_left_to_receive = g_num_blocks_in_file;

unsigned long num_unfinished_requests = 0;

/* A brief note on how the num_unfinished_requests variable is used:

* As mentioned earlier, in io_uring it is possible to have more requests in-flight than the

* size of the completion ring. In earlier kernels this could cause the completion queue to overflow.

* In later kernels there was an option added (IORING_FEAT_NODROP) which, when enabled, means that

* if a completion event occurs and the completion queue is full, then the kernel will internally

* store the event until the completion queue has room for more entries.

* Therefore, on newer kernels, it isn't necessary, strictly speaking, for the application to limit

* the number of in-flight requests. But, since it is almost certainly the case that an application

* can submit requests at a faster rate than the system is capable of servicing them, if we don't

* have some backpressure mechanism, then the application will just keep on submitting more and more

* requests, which will eventually lead to the system running out of memory.

* Setting a hard limit on the total number of in-flight requests serves as a backpressure mechanism

* to prevent the number of requests buffered in the kernel from growing without bound.

* The implementation is very simple: we increment num_unfinished_requests whenever a request is placed

* onto the submission queue, and decrement it whenever an entry is removed from the completion queue.

* Once num_unfinished_requests hits the limit that we set, then we cannot issue any more requests

* until we receive more completions, therefore the number of new completions that we receive is exactly

* equal to the number of new requests that we will place, thus ensuring that the number of in-flight

* requests can never exceed g_queuedepth.

*/

off_t next_file_offset_to_request = 0;

struct io_uring uring;

if (setup_io_uring_context(g_queuedepth, &uring)) {

puts("FAILED TO SET UP CONTEXT");

exit(1);

}

struct io_uring* ring = ů

while (num_blocks_left_to_receive) { // This loop consists of 3 steps:

// Step 1. Submit read requests.

// Step 2. Retrieve completions.

// Step 3. Run consumer.

/*

* Step 1: Make zero or more read requests until g_queuedepth limit is reached, or until the producer head reaches

* a cell that is not in the ALREADY_CONSUMED state (see my article/blog post for explanation).

*/

unsigned long num_unfinished_requests_prev = num_unfinished_requests; // The only purpose of this variable is to keep track of whether

// or not we added any new requests to the submission queue.

while (num_blocks_left_to_request) {

if (num_unfinished_requests >= g_queuedepth)

break;

if (g_ringbuf[producer_head].state != ALREADY_CONSUMED)

break;

/* expected_return_size is the number of bytes that we expect this read request to return.

* expected_return_size will be the block size until the last block of the file.

* when we get to the last block of the file, expected_return_size will be the size of the last

* block of the file, which is calculated in calculate_numblocks_and_size_of_last_block

*/

size_t expected_return_size = g_blocksize;

if (num_blocks_left_to_request == 1) // if we're at the last block of the file

expected_return_size = g_size_of_last_block;

add_read_request_to_submission_queue(ring, expected_return_size, next_file_offset_to_request);

next_file_offset_to_request += expected_return_size;

++num_unfinished_requests;

--num_blocks_left_to_request;

// We have added a request for the read syscall to write into the cell in the ringbuffer.

// The add_read_request_to_submission_queue has already marked it as REQUESTED_BUT_NOT_YET_COMPLETED,

// so now we just need to move the producer head to point to the next cell in the ringbuffer.

increment_buffer_index(&producer_head);

}

// If we added any read requests to the submission queue, then submit them.

if (num_unfinished_requests_prev != num_unfinished_requests) {

rc = io_uring_submit(ring);

if (rc < 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "io_uring_submit: %s\n", strerror(-rc));

exit(1);

}

}

/*

* Step 2: Remove all the items from the completion queue.

*/

bool first_iteration = 1; // On the first iteration of the loop, we wait for at least one cqe to be available,

// then remove one cqe.

// On each subsequent iteration, we try to remove one cqe without waiting.

// The loop terminates only when there are no more items left in the completion queue,

while (num_blocks_left_to_receive) { // Or when we've read in all of the blocks of the file.

struct io_uring_cqe *cqe;

if (first_iteration) { // On the first iteration we always wait until at least one cqe is available

rc = io_uring_wait_cqe(ring, &cqe); // This should always succeed and give us one cqe.

first_iteration = 0;

} else {

rc = io_uring_peek_cqe(ring, &cqe); // This will fail once there are no more items left in the completion queue.

if (rc == -EAGAIN) { // A return code of -EAGAIN means that there are no more items left in the completion queue.

break;

}

}

if (rc < 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "io_uring_peek_cqe: %s\n",

strerror(-rc));

exit(1);

}

assert(cqe);

// At this point we have a cqe, so let's see what our syscall returned.

struct my_custom_data *data = (struct my_custom_data*) io_uring_cqe_get_data(cqe);

// Check if the read syscall returned an error

if (cqe->res < 0) {

// we're not handling EAGAIN because it should never happen.

fprintf(stderr, "cqe failed: %s\n",

strerror(-cqe->res));

exit(1);

}

// Check if the read syscall returned an unexpected number of bytes.

if ((size_t)cqe->res != data->nbytes_expected) {

// We're not handling short reads because they should never happen on a disk-based filesystem.

if ((size_t)cqe->res < data->nbytes_expected) {

puts("panic: short read");

} else {

puts("panic: read returned more data than expected (wtf). Is the file changing while you're reading it??");

}

exit(1);

}

assert(data->offset_of_block_in_file % g_blocksize == 0);

// If we reach this point, then it means that there were no errors: the read syscall returned exactly what we expected.

// Since the read syscall returned, this means it has finished filling in the cell with ONE block of data from the file.

// This means that the cell can now be read by the consumer, so we need to update the cell state.

g_ringbuf[data->ringbuf_index].state = AVAILABLE_FOR_CONSUMPTION;

--num_blocks_left_to_receive; // We received ONE block of data from the file

io_uring_cqe_seen(ring, cqe); // mark the cqe as consumed, so that its slot can get reused

--num_unfinished_requests;

if (g_process_in_inner_loop)

resume_consumer();

}

/* Step 3: Run consumer. This might be thought of as handing over control to the consumer "thread". See my article/blog post. */

resume_consumer();

}

resume_consumer();

close(g_filedescriptor);

io_uring_queue_exit(ring);

// Finalize the hash. BLAKE3_OUT_LEN is the default output length, 32 bytes.

uint8_t output[BLAKE3_OUT_LEN];

blake3_hasher_finalize(&g_hasher, output, BLAKE3_OUT_LEN);

// Print the hash as hexadecimal.

printf("BLAKE3 hash: ");

for (size_t i = 0; i < BLAKE3_OUT_LEN; ++i) {

printf("%02x", output[i]);

}

printf("\n");

}

static void process_cmd_line_args(int argc, char* argv[])

{

if (argc != 9) {

printf("%s: infile g_blocksize g_queuedepth g_use_o_direct g_process_in_inner_loop g_numbufs g_use_iosqe_io_drain g_use_iosqe_io_link\n", argv[0]);

exit(1);

}

g_blocksize = atoi(argv[2]) * 1024; // The command line argument is in KiBs

g_queuedepth = atoi(argv[3]);

if (g_queuedepth > 32768)

puts("Warning: io_uring queue depth limit on Kernel 6.1.0 is 32768...");

g_use_o_direct = atoi(argv[4]);

g_process_in_inner_loop = atoi(argv[5]);

g_numbufs = atoi(argv[6]);

g_use_iosqe_io_drain = atoi(argv[7]);

g_use_iosqe_io_link = atoi(argv[8]);

}

static void open_and_get_size_of_file(const char* filename)

{

if (g_use_o_direct){

g_filedescriptor = open(filename, O_RDONLY | O_DIRECT);

puts("opening file with O_DIRECT");

} else {

g_filedescriptor = open(filename, O_RDONLY);

puts("opening file without O_DIRECT");

}

if (g_filedescriptor < 0) {

perror("open file");

exit(1);

}

if (get_file_size(g_filedescriptor, &g_filesize)){

puts("Failed getting file size");

exit(1);

}

}

static void calculate_numblocks_and_size_of_last_block()

{

// this is the mathematically correct way to do ceiling division

// (assumes no integer overflow)

g_num_blocks_in_file = (g_filesize + g_blocksize - 1) / g_blocksize;

// calculate the size of the last block of the file

if (g_filesize % g_blocksize == 0)

g_size_of_last_block = g_blocksize;

else

g_size_of_last_block = g_filesize % g_blocksize;

}

static void allocate_ringbuf()

{

// We only make 2 memory allocations in this entire program and they both happen in this function.

assert(g_blocksize % ALIGNMENT == 0);

// First, we allocate the entire underlying ring buffer (which is a contiguous block of memory

// containing all the actual buffers) in a single allocation.

// This is one big piece of memory which is used to hold the actual data from the file.

// The buf_addr field in the my_custom_data struct points to a buffer within this ring buffer.

unsigned char* ptr_to_underlying_ring_buffer;

// We need aligned memory, because O_DIRECT requires it.

if (posix_memalign((void**)&ptr_to_underlying_ring_buffer, ALIGNMENT, g_blocksize * g_numbufs)) {

puts("posix_memalign failed!");

exit(1);

}

// Second, we allocate an array containing all of the my_custom_data structs.

// This is not an array of pointers, but an array holding all of the actual structs.

// All the items are the same size, which makes this easy

g_ringbuf = (struct my_custom_data*) malloc(g_numbufs * sizeof(struct my_custom_data));

// We partially initialize all of the my_custom_data structs here.

// (The other fields are initialized in the add_read_request_to_submission_queue function)

off_t cur_offset = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < g_numbufs; ++i) {

g_ringbuf[i].buf_addr = ptr_to_underlying_ring_buffer + cur_offset; // This will never change during the runtime of this program.

cur_offset += g_blocksize;

// g_ringbuf[i].bufsize = g_blocksize; // all the buffers are the same size.

g_ringbuf[i].state = ALREADY_CONSUMED; // We need to set all cells to ALREADY_CONSUMED at the start. See my article/blog post for explanation.

g_ringbuf[i].ringbuf_index = i; // This will never change during the runtime of this program.

}

}

int main(int argc, char *argv[])

{

assert(sizeof(size_t) >= 8); // we want 64 bit size_t for files larger than 4GB...

process_cmd_line_args(argc, argv); // we need to first parse the command line arguments

open_and_get_size_of_file(argv[1]);

calculate_numblocks_and_size_of_last_block();

allocate_ringbuf();

// Initialize the hasher.

blake3_hasher_init(&g_hasher);

// Run the main loop

producer_thread();

}

Basically, my program reads a file from disk and then hashes it. In slightly more detail, my program issues read requests for blocks of the file, and then hashes the returned file blocks after they arrive. So, it is pretty much the simplest program imaginable that uses io_uring.

To really understand my program, the reader needs to know that io_uring

is an asynchronous API which consists of two rings, a submission queue

(SQ) and a completion queue (CQ). The way you use it is simple: you put

your requests, which are called Submission Queue Entries (SQEs), into

the SQ, then you call submit(), and then you poll or wait on the CQ for

completions aka Completion Queue Events (CQEs). The important thing to

remember about io_uring is that by default, requests submitted to io_uring may be completed in any order. There are two flags that you can use to force io_uring to complete the requests in order (IOSQE_IO_DRAIN and IOSQE_IO_LINK), but they greatly reduce the performance of the program, thus defeating the entire purpose of using io_uring

in the first place (of course, this makes sense given how they work -

these flags make it so that the next sqe won’t be started until the

previous one is finished, which kind of almost defeats the entire point

of having an asynchronous API…actually I found that the IOSQE_IO_LINK

didn’t even work - I was still getting out of order completions - but

it did slow down my program by a lot…that was on an earlier version of

my program though) - you can actually easily check this for yourself: my

program exposes those flags as command line parameters. I actually

tried to use those flags to begin with, and only when I could not obtain

acceptable performance while using the flags did I finally accept that I

had to just deal with out-of-order completions. Actually, there are

some use cases out there which do not need file blocks to be processed

in order (such as file copying, for example). Unfortunately, file

hashing is not one of those use cases - when hashing a file, we usually

do need to process the blocks of the file in order (at least, the BLAKE3

C API doesn’t offer the option to hash blocks in arbitrary order).

Therefore, we need some way to deal with out-of-order completions.

So, the simplest way to deal with this that I could think of was to just allocate one array big enough to hold the entire file in memory, then, whenever a completion arrives, we put it into the array at the appropriate slot in the array. For example, if we have a file that consists of 100 blocks, then we will allocate an array with 100 slots, and when we receive the completion for, say, the 5th block, then we will place that completion into the 5th slot in the array. This way, the file hashing function can simply iterate over this array, waiting for the next slot in the array to be filled with a completion before continuing. I actually made both a single-threaded as well as a multithreaded implementation of the approach described above, and they were actually very close to the fastest possible performance, but they did not reach the speed limit.

In order to reach the speed limit, I had to make one more optimization. And that optimization is to use a fixed-size ring buffer instead of allocating a single buffer that is big enough to hold all of the blocks of the file. Besides being faster, this also had the advantage of using less memory - that actually was the original reason I implemented it - I didn’t think that it would speed up my program, I only implemented it because my computer kept running out of memory when I was using the program to hash large files. So I was quite pleasantly surprised to discover that it actually improved the performance of my program.

Now, the ring buffer implementation is a little bit more complicated, so let’s think about the question: What is the correctness property for this algorithm? I thought of this:

The consumer will process all the blocks of the file exactly once each and in order.

It is actually trivial to write a consumer that will process the blocks of the file exactly once each and in order. The tricky part is making sure that it will process ALL of the blocks of the file. How do we ensure that it will process the blocks of the file exactly once each and in order? Simple: with the following implementation: the consumer simply iterates over the array and looks at the state and block offset of the next cell - if the state of the cell is “ready to be processed” and the block offset is that of the block that it wants, then the consumer will consume it. All the consumer needs to do is to internally keep track of the offset of the last block it has consumed, and add the block size to that offset to get the offset of the next block that it wants.

But there is another consideration that we must not forget - the queue depth. More precisely, as I explained in the code comments, it is essentially the number of requests that are in-flight. Why is this important? Because io_uring is an asynchronous API - the submit returns instantly, so you can just keep putting more and more requests in, submitting them, and (at least on some versions of the kernel) eventually the system will run out of memory. So we need to limit the number of requests that can be in-flight at any given moment, and the simplest way to do this is to use a counter - we decrement the counter whenever we issue a request and we increment the counter whenever we receive a completion. When the counter hits 0 we stop issuing new requests and just wait for completions. In this way we can ensure that the number of requests that are in-flight can never exceed the initial size of the counter.

With this design, we can’t issue requests for the entire file at a time. If the file consists of, say, 1 million blocks, we can’t just issue 1 million read requests at the start of the program and just poll for completions, since we can’t allow more than a small number of in-flight requests at any given moment. Instead, we have to limit ourselves to sending requests for a few blocks at a time, and waiting for at least one request to complete before sending any new requests.

Let’s give an example. Suppose we have a ring buffer that has 5 slots, and a queue depth limit of 3, meaning we can only have up to 3 in-flight requests at a time. At the beginning of the program, we can issue 3 requests. Now the question is which 3 do we want to issue for? The answer is quite obvious: the first 3 blocks (which corresponds to the first 3 slots), and we want to issue them in the order of block 0, then block 1, then block 2. Why? Because even though there is no guarantee that the requests will finish in the order that they were issued, the kernel will at least attempt those requests in the order that they were issued (since it is a ring buffer after all). And we want the first block to finish first, because that would allow the consumer to begin working as soon as possible - for the sake of efficiency, we want the consumer to always be processing some data, so we want the first block to return first (rather than, say, the second block to return first). So, taking this principle further, it means that we want to issue requests in the order that would unblock the consumer as soon as possible. That means that, if the consumer is currently waiting for block i to become “available for processing” then the producer must issue a request for block i before it issues a request for any other blocks. Reasoning forward, the producer should also issue the request for block i+1 before it issues the request for the block i+2, and it should issue the request for block i+2 before it issues a request for block i+3, and so on. Therefore, the producer should issue requests for blocks in the order 0, 1, 2, 3, … and so on until the last block.

So, we now have that the consumer has what is essentially a “consume head” that continually moves forward to the next cell in the ringbuffer whenever it can, but this is also the case for the “producer head” which I think is more accurately called the “requester head”. Thus, we have 2 pointers:

The “requester head” points to the slot for which the producer will issue the next read request - the read syscall will then fill in that slot with the block from the file. Once the producer has issued a request for a block, it should then issue a request for the next block, as I explained, unless it cannot. When can it not? There are 2 cases: Firstly, if the number of request in-flight has reached the limit, then it can no longer issue any new requests until we get a completion. Secondly, it cannot issue a request if the next slot is not available for it to issue a request on. It is important to remember that blocks are mapped to slots in the ring buffer, and that issuing a request for the next block in the file means that it needs the next slot in the ring buffer to be “free” i.e. can be used for being filled in. Now, if the consumer is currently reading that slot, then obviously it cannot issue a request for that slot. But there are also other situations where it cannot issue a request for that slot, for example, if it has already issued a request for that slot, but the consumer hasn’t read that slot yet. I think it’s easier to understand this with an example:

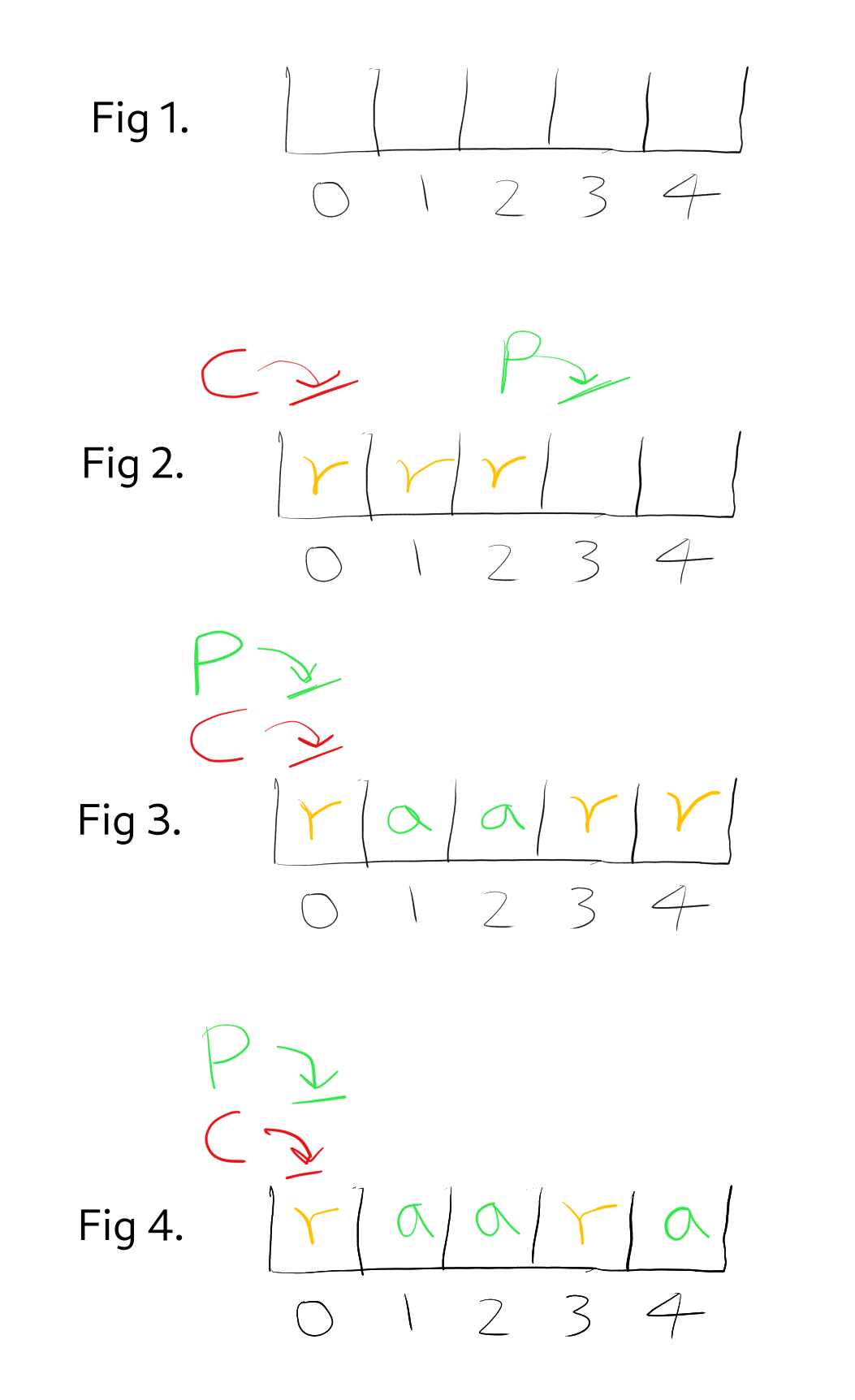

There are basically two cases. The first is when the queue depth is smaller than the number of slots in the ring buffer, and the second is when the queue depth is greater than the number of slots in the ring buffer. Let’s go through them in turn. See this diagram:

To begin with, suppose we set the queue depth to 3 and the ring buffer size to 5 slots. Initially (Fig 1.) the ring buffer is empty, so the consumer cannot move but the producer can start making requests, so it does. Since the queue depth is 3 that means the producer can make up to 3 requests to begin with. So now (Fig 2.) we have made 3 requests, one request each for blocks 0, 1, and 2, corresponding to slots 0, 1, and 2. Here I use the symbol “r” to represent slots for which we have made a read request, but the read request hasn’t yet returned. This means that the consumer cannot read them, since the slots don’t contain the data yet. Now, suppose the read requests for slots 1 and 2 return, but the read request for slot 0 still hasn’t returned (Fig 3.). This means that even though slots 1 and 2 are available for reading, the consumer cannot advance because it is still blocked waiting for slot 0 to become available for processing. But, since we have received completions for blocks 1 and 2, that means we can issue 2 more requests, so we issue requests for the next 2 blocks for which we haven’t yet issued requests, which are slots 3 and 4. Now (Fig 4.) suppose that the read call returns for slot 4, but slot 0 is still waiting. But now, the number of requests in flight is only 2, which means the producer is not prevented by the queue depth from issuing more read requests. However, the consumer is still blocked waiting for slot 0 to become available for consumption. At this point, would it be okay for the producer to overwrite it? Now, the producer wants to issue the read request for block 5, to be written into slot 0, but the consumer hasn’t seen block 0 yet, so clearly the producer should NOT make a request for slot 0 until the consumer has processed it. From this we can extrapolate a general principle. Earlier we mapped each slot to a list of blocks, e.g. if the ring buffer has 5 slots then we mapped slot 0 to block 0, block 5, block 10, block 15 and so on. And I hope the diagram has shown that we need to make sure to not request block 5 before the consumer is finished with block 0, because they both map to the same slot, meaning if we requested block 5 before the consumer is finished with block 0, then we would overwrite the slot where block 0 was going to be stored. More generally, by ensuring that we ONLY request the “next” block for each slot AFTER the consumer is finished with the “previous” block for that slot, we ensure that we don’t overwrite blocks that are being processed or haven’t been processed yet.

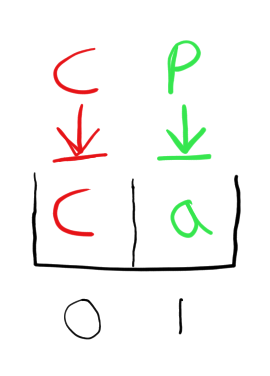

So that’s one way to look at it. Another way is to think in terms of the cell states. In the diagram we have shown 2 states that a cell could be in - the “r” state and the “a” state. Now, we can ask: what state must a cell be in in order for the producer to be allowed to make a request for that cell? Well, if the cell is in the “r” state, then that means that the producer has already made a request for that cell, and that the consumer hasn’t yet consumed that cell (obviously, because it’s not available for consumption yet), which means that if we overwrite that cell, that means we’re going to be overwriting a block for which we have already made a request. The case I’m talking about is when the producer moves to the next cell, and finds that that cell is in the “r” state - this can only mean one thing, which is that the producer has gone the full way around the ring buffer and is now looking at a cell which is waiting to receive the “previous” block for that slot compared to the one that the producer wants to request next, and we just explained that it would be an error to issue a request in this case. Actually, I think this way of looking at it - in terms of cell states - is easier to reason about. So, how many cell states are there? I can think of a few:

But do we really need to represent all of these states? Well, what are the states for in the end? They’re there to ensure the correctness of the program, which is:

To ensure these correctness properties, all we need to do is to ensure the following:

I used the word “exactly” to convey the two requirements: that the consumer/producer should not advance when it’s not safe to advance (correctness), and also that it must advance as soon as it is safe to do so (efficiency). Since that is the only purpose of having cell states, we can therefore boil the states down to just these 4:

In fact, state 3 cannot exist, because we cannot have a cell being simultaneously accessed by both the consumer and the producer - that would be a data race (since the producer is writing to the cell while the consumer is reading it) and therefore undefined behavior. So really there can only be 3 states:

We can then map the states that we have mentioned previously into those 3 states.

So, now we have the complete lifecycle for a cell in the ring buffer: At the start of the program, all the cells are empty, so the consumer cannot consume any of them but the producer can issue requests for them, so initially we need to mark every block in the array as in the “c” state so that the producer will issue requests for them but the consumer will not try to consume them. Once the producer has issued a request for that cell, then that cell will go into the “r” state until the read request completes. Why? Because as explained earlier, if the producer has issued a read request for a cell, but the read request hasn’t returned yet, then the producer should not overwrite that cell, and the consumer can’t process it either since it hasn’t been filled yet, so the “r” state is appropriate here. Next, the read request returns, so we change the cell to the “a” state. Why? Because after the read request returns for a cell, that cell can now be processed by the consumer, but we don’t want the producer to issue a request for that cell before the consumer is done with it, therefore the “a” state is appropriate here. While the consumer is processing the cell, the producer should not issue a request for it, so it is ok for the cell to remain in the “a” state. When the consumer is done with the cell, now the producer can issue a request for it, but the consumer should not attempt to consume the cell again (since it has already hashed the file block, passing it to the hash update function again would cause an incorrect result), therefore we must transition the cell to the “c” state. And finally, once the producer head reaches the cell again, the cycle begins anew.

But how does this design satisfy the correctness properties that we want the program to have? What we’d like is some kind of proof that the consumer won’t get stuck. So, suppose the consumer head is currently at slot i. What would stop it from moving to slot i+1? The only thing would be if the current slot is not in the “a” state - if it’s in the “a” state, then the consumer would process it and then move on to the next slot. So all we need to do is to show that if a slot is in a non-“a” state, that it will eventually transition into the “a” state. So how do we show that? Well there are only two non-“a” states: “r” and “c”. If a slot is in the “r” state, then it is just waiting for the read syscall to return, and so when that read syscall returns then the state will turn into “a”, so all “r” cells will turn into “a” eventually. If a slot is in the “c” state, then we need some guarantee that the producer will eventually turn it into the “r” state. This also is actually very easy to show - the producer will continually move across the array turning all "c"s into "r"s, only stopping if the number of requests in-flight has hit the limit, or if the producer has reached a cell that is not in the “c” state (note that here I’m talking about the conceptual high-level abstract design, rather than any specific implementation). The only thing we need to prove, then, is that the producer will never get blocked by a non-“c” cell from reaching a “c” cell. Well, it is probably easier to see it with a diagram:

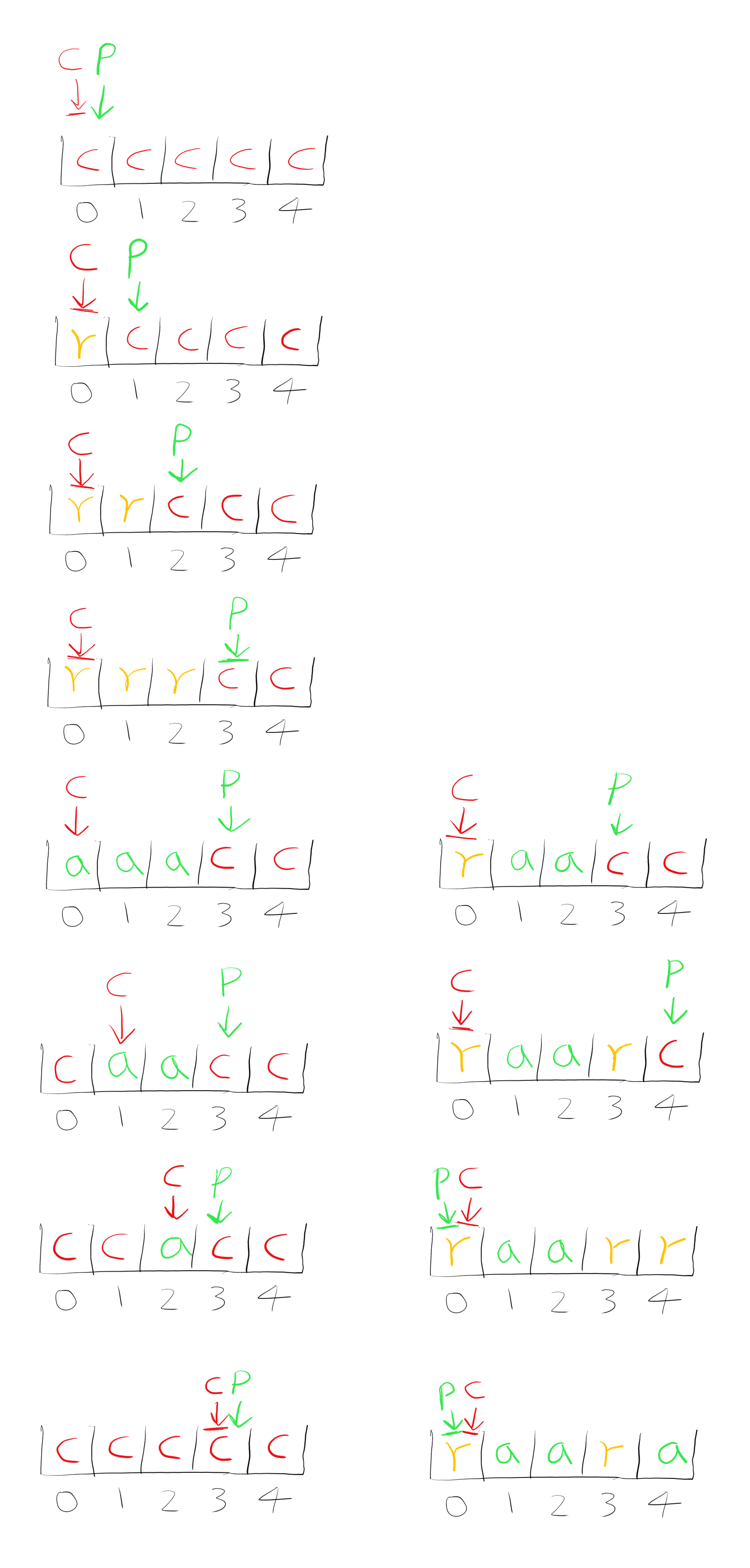

The above diagram shows a ring buffer of size 5 with a queue depth of 3 (the diagram shows what happens when the queue depth is smaller than the size of the ring buffer - it just means that the requester loop won’t issue more requests until more completions arrive. As you can see, as the producer head iterates through the ring buffer one slot at a time, each time requesting for the next block of the file, so the consumer follows the producer head, and so every time the consumer processes a new slot, that is the next block of the file. If the queue depth is greater than or equal to the size of the ring buffer, then the situation is simpler: the requester loop will just issue requests for every cell in the array that is in the “c” state). At the start, both the consumer and producer heads are pointing to the first slot, which is slot 0. Now, at this point, the consumer head is stuck and can’t move, but the producer head can move, so the producer head moves first - it submits the requests, and the producer head moves 3 slots over, until it hits the queue depth, then we check for completions. Now here is where different things can happen. On the left hand side is what would happen if all 3 requests returned right there and then. In that case, all the slots that were in the “r” state are now in the “a” state, so when we run the consumer, the consumer will happily iterate across all of those “a” slots, processing them as it goes along, turning them into “c” slots when it has finished processing them, and finally it will reach slot 3 which is still in the “c” state, so now the consumer stops and returns control back to the producer. In the alternative universe where the slot 0 remained in the “r” state, then the consumer would still be waiting for slot 0, and so hands control back to the producer, who will then proceed to issue requests for slots 3 and 4 since the number of in flight requests dropped below the queue depth. Then we ask for completions, and see that slot 4 has returned, so we transition it to “a”, and we try to run the consumer again but it is still waiting for slot 0, then we go back to the producer and it’s also waiting for slot 0.

So, I wanted to prove that there can never be a case where the producer will get permanently blocked, and that’s because, as the diagram shows, as the producer moves across the ring buffer it leaves behind a trail of cells in the “r” state which eventually transition into the “a” state. And similarly, as the consumer moves across the ring buffer it leaves behind a trail of cells in the “c” state. Therefore we have an assurance that the “c” cells and the “a”/“r” cells do not “mix” - all of the cells “behind” the consumer head but “in front” of the producer head are “c”, while all of the cells “behind” the producer head but “in front” of the consumer head are "r"s or "a"s. Therefore, as the diagram shows, when the producer head reaches a slot in the “r” or “a” state, then that means it has caught up to the consumer head, since if it was behind the consumer head then it would be seeing cells in the “c” state. Therefore, that means it is at the same cell where the consumer head is pointing to. If the cell is in the “a” state then the consumer will process it turning it into the “c” state, and if it’s in the “r” state then it will eventually turn into the “a” state, and then the consumer will process it turning it into the “c” state.

The reasoning above is for a generic multi-threaded implementation where the producer and consumer are on separate threads. But what about our single-threaded ring buffer implementation? Well, actually the sequence of events that I’ve shown above is consistent with the order of events in my single-threaded ringbuffer implementation, which consists of a main loop that consists of 3 sub-loops which are executed one after another - a “requester loop” which issues requests, a “completion loop” which checks for completions, and finally a “consumer loop” which runs the consumer. I want to show that this execution order can NEVER get stuck. So, to begin with, the requester loop may issue zero or more requests. As we discussed, it will issue requests until either the number of requests in flight reaches the queue depth, or until the producer head reaches a slot that is not in the “c” state. So this loop runs very fast and can never get stuck. Next, we wait until the completion queue contains at least one completion, and then we remove all of the completions from the completion queue. So, can this loop get stuck? That could only happen if we were waiting forever to see a completion. And that would only be possible if there are no cells in the “r” state. Why? Because if there is at least one cell that is in the “r” state, then the read syscall will eventually return and we will get a completion event. So, is it possible for there to be no cells in the “r” state when we wait on the completion queue?

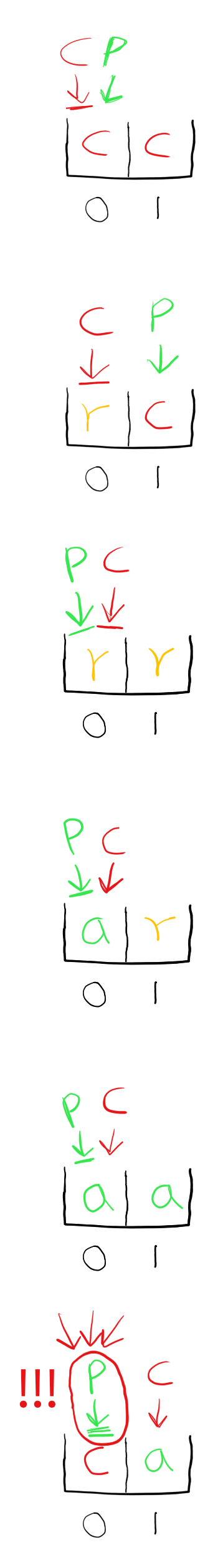

Let’s think about the conditions required for that to happen:

So, what is the scenario where the requester loop didn’t issue any requests, but there are also no requests in flight? That is only possible if the cell that the producer head was pointing to was not in the “c” state. And since there are no cells in the “r” state, then that means the cell must be in the “a” state. I have previously explained that the only situation where this is possible is if the producer head has caught up to the consumer head (since the consumer leaves behind a trail of cells in the “c” state behind the consumer head). This means that the producer and consumer heads are pointing to the same cell. Now, since the requester loop did not issue any requests that means the producer head did not move from the start to the end of the requester loop, so at the very start of the requester loop, both the producer and consumer heads were pointing to the same cell, which is in the “a” state. That means that the previous run of the consumer loop must have ended with the consumer head pointing to a cell that is in the “a” state (it couldn’t have been in the “r” state because we only update the cell state from “r” to “a” in the completion loop, so the state of a cell cannot change from “r” to “a” from the start of the consumer loop to the end of the requester loop. Another way to think about this is that if the consumer loop did end with the consumer head pointing to a cell in the “r” state, then the cell would remain in the “r” state throughout the requester loop too, since the requester loop cannot turn “r” cells into “a” cells, which means the cell would be in the “r” state when entering the completion loop, which I’ve just explained cannot be the case here), which is impossible because the consumer will try to process all cells that are in the “a” state turning them into the “c” state, therefore it is impossible for the consumer head to be pointing at a cell that is in the “a” state at the end of the consumer loop.

Therefore we have proved that it is impossible for the completion loop to get stuck. The final loop, the consumer loop, also cannot get stuck because it simply loops through the array processing cells until it gets to a cell that is not in the “c” state, at which point it just terminates.

So, we have established that our single-threaded ring buffer implementation can never get stuck. What about correctness? Well, since we’re ensuring correctness by using the states, so we just need to ensure that the states are always correct. In the single-threaded implementation, the three loops are executed one after the other. This ensures that the states are always correct. When the requester loop terminates, the cells that it touched, i.e. transitioned into the “r” state, really are in the “r” state. And when the completion loop terminates, the cells that it touched, i.e. transitioned into the “a” state, really are in the “a” state. And when the consumer loop terminates, the cells that it touched, i.e. transitioned into the “c” state, really are in the “c” state. And since the loops run one after the other, it is guaranteed that the cell states are always correct from the perspective of each loop, so, for example, the consumer be confident that the cells that are in the “a” state really are available for it to process. In a multi-threaded implementation, synchronization is required in order to prevent the producer thread and the consumer thread from accessing cell states simultaneously, since that would be a data race and therefore undefined behavior.

Now, what about reissuing requests? For example, if a read request failed, or if you got a short read, then you may want to re-issue the read request (with updated parameters). Now, in my program, the consumer consumes in order while the producer also makes requests in order, but if you want to re-issue a request, then that means issuing a request for a block that you have already requested previously. But this is actually totally fine. Why is it okay? Because my program doesn’t actually care about the order in which requests are issued. All it cares about is that the producer and consumer heads move across the array one cell at a time, that the cells are mapped to the correct blocks, and that the state of the cell is always correct. That is to say, if a cell transitions into the “a” state then it MUST be okay for the consumer to process it. This is actually perfectly consistent with the use case where a read request returns an error or an incomplete read and you want to reissue the request - in that case, you just don’t transition the cell into the “a” state, instead, you keep it in the “r” state and just re-issue the request. From the perspective of the consumer as well as the producer, it just looks like the cell is staying in the “r” state longer than usual. You can implement this in the completion loop - if the syscall return value (the res field in the cqe) is not as expected, then you can just re-issue the request right there.

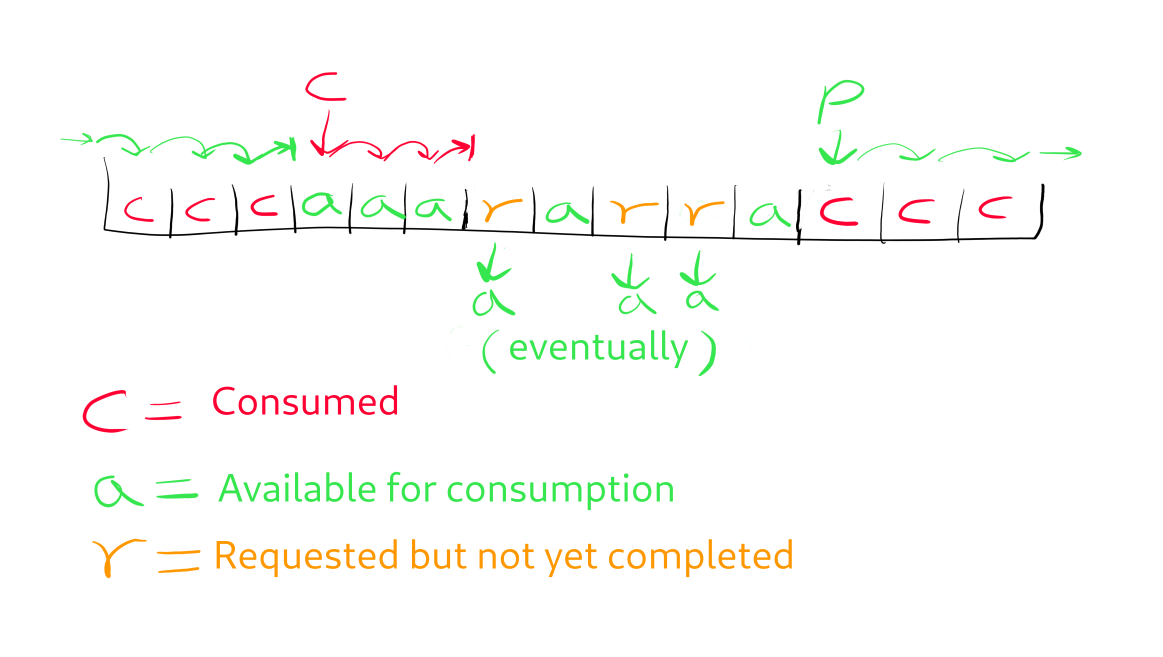

Here is a simple overview of how it works:

So, the producer is continually waiting for the next slot to become “already consumed” while the consumer is continually waiting for the next slot to become “available for consumption”. The requester leaves behind a trail of slots that are “requested but not yet completed” which will all eventually turn into “available for consumption” while the consumer leaves behind a trail of slots that are “already consumed”.

Here is a diagram to illustrate this:

So in the diagram above, the P arrow denotes the position of the producer’s “requester head” (it’s a producer conceptually - doesn’t have to be an actual thread) while the C arrow denotes the consumer’s “consumer head”. As you can see, the producer’s “requester head” moves forward as long as there is a “c” (“already consumed”) slot in front of it while the consumer’s “consumer head” also moves forward as long as there is a “a” (“available for consumption”). So we can see that eventually, all the slots “behind” the requester head will become “a” while all the slots “behind” the consumer head are immediately marked as “c”. So we have the property that all the slots “in front of” the consumer head but “behind” the producer head will eventually become “a” while all of the slots “behind” the consumer head but “in front of” the producer head are always “c”. In the beginning all the slots are marked as “c” so the producer head will move first while the consumer head cannot move. Then as the producer leaves behind a trail of “r” some of those "r"s will turn into "a"s and so the consumer head will start moving too. Thus we established the main cycle where the producer moves forward consuming the "c"s and leaving behind "r"s which turn into "a"s while the consumer follows behind consuming the "a"s and turning them back into "c"s.

In this section, I will explain how the multi-threaded implementation differs from the single-threaded implementation and why I think it’s correct and won’t get stuck. In order to understand this section, you need to have read the previous sections, which explain how the single-threaded implementation works and why I think it’s correct and won’t get stuck.

Here’s the code for the multi-threaded version of my program:

/* SPDX-License-Identifier: MIT */

/*

* Compile with: g++ -Wall -O3 -D_GNU_SOURCE liburing_b3sum_multithread.cc -luring libblake3.a -o liburing_b3sum_multithread

* For an explanation of how this code works, see my article/blog post: https://1f604.com/b3sum

*

* Note: the comments in this program are copied unchanged from the single-threaded implementation in order to make it easier for a reader using `diff` to see the code changes from the single-thread version

*

* This program is a modified version of the liburing cp program from Shuveb Hussain's io_uring tutorial.

* Original source code here: https://github.com/axboe/liburing/blob/master/examples/io_uring-cp.c

* The modifications were made by 1f604.

*

* The official io_uring documentation can be seen here:

* - https://kernel.dk/io_uring.pdf

* - https://kernel-recipes.org/en/2022/wp-content/uploads/2022/06/axboe-kr2022-1.pdf

*

* Acronyms: SQ = submission queue, SQE = submission queue entry, CQ = completion queue, CQE = completion queue event

*/

#include "blake3.h"

#include "liburing.h"

#include <stdio.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <assert.h>

#include <sys/ioctl.h>

// Multithreading stuff

#include <atomic>

#include <thread>

/* Constants */

static const int ALIGNMENT = 4 * 1024; // Needed only because O_DIRECT requires aligned memory

/* ===============================================

* ========== Start of global variables ==========

* ===============================================

* Declared static because they are only supposed to be visible within this .c file.

*

* --- Command line options ---

* The following variables are set by the user from the command line.

*/

static int g_queuedepth; /* This variable is not really the queue depth, but is more accurately described as

* "the limit on the number of incomplete requests". Allow me to explain.

* io_uring allows you to have more requests in-flight than the size of your submission

* (and completion) queues. How is this possible? Well, when you call io_uring_submit,

* normally it will submit ALL of the requests in the submission queue, which means that

* when the call returns, your submission queue is now empty, even though the requests

* are still "in-flight" and haven't been completed yet!

* In earlier kernels, you could overflow the completion queue because of this.

* Thus it says in the official io_uring documentation (https://kernel.dk/io_uring.pdf):

* Since the sqe lifetime is only that of the actual submission of it, it's possible

* for the application to drive a higher pending request count than the SQ ring size

* would indicate. The application must take care not to do so, or it could risk

* overflowing the CQ ring.

* That is to say, the official documentation recommended that applications should ensure

* that the number of in-flight requests does not exceed the size of the submission queue.

* This g_queuedepth variable is therefore a limit on the total number of "incomplete"

* requests, which is the number of requests on the submission queue plus the number of

* requests that are still "in flight".

* See num_unfinished_requests for details on how this is implemented. */

static int g_use_o_direct; // whether to use O_DIRECT

static int g_process_in_inner_loop; // whether to process the data inside the inner loop

static int g_use_iosqe_io_drain; // whether to issue requests with the IOSQE_IO_DRAIN flag

static int g_use_iosqe_io_link; // whether to issue requests with the IOSQE_IO_LINK flag

//static int g_use_ioring_setup_iopoll; // when I enable either IORING_SETUP_SQPOLL or IORING_SETUP_IOPOLL, on my current system,

//static int g_use_ioring_setup_sqpoll; // it turns my process into an unkillable zombie that uses 100% CPU that never terminates.

// when I was using encrypted LVM, it just gave me error: Operation not supported.

// I decided to not allow users to enable these options because I didn't want them

// to accidentally launch an unkillable never-ending zombie process that uses 100% CPU.

// I observed this problem in fio too when I enabled --hipri on fio, it also turned into

// an unkillable never-ending zombie process that uses 100% CPU.

static size_t g_blocksize; // This is the size of each buffer in the ringbuf, in bytes.

// It is also the size of each read from the file.

static size_t g_numbufs; // This is the number of buffers in the ringbuf.

/* --- Non-command line argument global variables --- */

blake3_hasher g_hasher;

static int g_filedescriptor; // This is the file descriptor of the file we're hashing.

static size_t g_filesize; // This will be filled in by the function that gets the file size.

static size_t g_num_blocks_in_file; // The number of blocks in the file, where each block is g_blocksize bytes.

// This will be calculated by a ceiling division of filesize by blocksize.

static size_t g_size_of_last_block; // The size of the last block in the file. See calculate_numblocks_and_size_of_last_block.

static int producer_head = 0; // Position of the "producer head". see explanation in my article/blog post

static int consumer_head = 0; // Position of the "consumer head". see explanation in my article/blog post

#define AVAILABLE_FOR_CONSUMPTION 1

#define ALREADY_CONSUMED 2

#define REQUESTED_BUT_NOT_YET_COMPLETED 3

struct my_custom_data { // This is the user_data associated with read requests, which are placed on the submission ring.

// In applications using io_uring, the user_data struct is generally used to identify which request a

// completion is for. In the context of this program, this structure is used both to identify which

// block of the file the read syscall had just read, as well as for the producer and consumer to

// communicate with each other, since it holds the cell state.

// This can be thought of as a "cell" in the ring buffer, since it holds the state of the cell as well

// as a pointer to the data (i.e. a block read from the file) that is "in" the cell.

// Note that according to the official io_uring documentation, the user_data struct only needs to be

// valid until the submit is done, not until completion. Basically, when you submit, the kernel makes

// a copy of user_data and returns it to you with the CQE (completion queue entry).

unsigned char* buf_addr; // Pointer to the buffer where the read syscall is to place the bytes from the file into.

size_t nbytes_expected; // The number of bytes we expect the read syscall to return. This can be smaller than the size of the buffer

// because the last block of the file can be smaller than the other blocks.

//size_t nbytes_to_request; // The number of bytes to request. This is always g_blocksize. I made this decision because O_DIRECT requires

// nbytes to be a multiple of filesystem block size, and it's simpler to always just request g_blocksize.

off_t offset_of_block_in_file; // The offset of the block in the file that we want the read syscall to place into the memory location

// pointed to by buf_addr.

std::atomic_int state; // Describes whether the item is available to be hashed, already hashed, or requested but not yet available for hashing.

int ringbuf_index; // The slot in g_ringbuf where this "cell" belongs.

// I added this because once we submit a request on submission queue, we lose track of it.

// When we get back a completion, we need an identifier to know which request the completion is for.

// Alternatively, we could use something to map the buf_addr to the ringbuf_index, but this is just simpler.

};

// multithreading function

static void update_cell_state(struct my_custom_data* data, int new_state) { // State updates need to be synchronized because both threads look at the state

// In effect they communicate via state updates.

// both the consumer and producer threads block/wait for state change to continue

data->state = new_state;

}

struct my_custom_data* g_ringbuf; // This is a pointer to an array of my_custom_data structs. These my_custom_data structs can be thought of as the

// "cells" in the ring buffer (each struct contains the cell state), thus the array that this points to can be

// thought of as the "ring buffer" referred to in my article/blog post, so read that to understand how this is used.

// See the allocate_ringbuf function for details on how and where the memory for the ring buffer is allocated.

/* ===============================================

* =========== End of global variables ===========

* ===============================================*/

static int setup_io_uring_context(unsigned entries, struct io_uring *ring)

{

int rc;

int flags = 0;

rc = io_uring_queue_init(entries, ring, flags);

if (rc < 0) {

fprintf(stderr, "queue_init: %s\n", strerror(-rc));

return -1;

}

return 0;

}

static int get_file_size(int fd, size_t *size)

{

struct stat st;

if (fstat(fd, &st) < 0)

return -1;

if (S_ISREG(st.st_mode)) {

*size = st.st_size;

return 0;

} else if (S_ISBLK(st.st_mode)) {

unsigned long long bytes;

if (ioctl(fd, BLKGETSIZE64, &bytes) != 0)

return -1;

*size = bytes;

return 0;

}

return -1;

}

static void add_read_request_to_submission_queue(struct io_uring *ring, size_t expected_return_size, off_t fileoffset_to_request)

{

assert(fileoffset_to_request % g_blocksize == 0);

int block_number = fileoffset_to_request / g_blocksize; // the number of the block in the file

/* We do a modulo to map the file block number to the index in the ringbuf

e.g. if ring buf_addr has 4 slots, then

file block 0 -> ringbuf index 0

file block 1 -> ringbuf index 1

file block 2 -> ringbuf index 2

file block 3 -> ringbuf index 3

file block 4 -> ringbuf index 0

file block 5 -> ringbuf index 1

file block 6 -> ringbuf index 2

And so on.

*/

int ringbuf_idx = block_number % g_numbufs;

struct my_custom_data* my_data = &g_ringbuf[ringbuf_idx];

assert(my_data->ringbuf_index == ringbuf_idx); // The ringbuf_index of a my_custom_data struct should never change.

my_data->offset_of_block_in_file = fileoffset_to_request;

assert (my_data->buf_addr); // We don't need to change my_data->buf_addr since we set it to point into the backing buffer at the start of the program.

my_data->nbytes_expected = expected_return_size;

update_cell_state(my_data, REQUESTED_BUT_NOT_YET_COMPLETED);

/*my_data->state = REQUESTED_BUT_NOT_YET_COMPLETED; /* At this point:

* 1. The producer is about to send it off in a request.

* 2. The consumer shouldn't be trying to read this buffer at this point.

* So it is okay to set the state to this here.

*/

struct io_uring_sqe* sqe = io_uring_get_sqe(ring);

if (!sqe) {

puts("ERROR: FAILED TO GET SQE");

exit(1);

}

io_uring_prep_read(sqe, g_filedescriptor, my_data->buf_addr, g_blocksize, fileoffset_to_request);

// io_uring_prep_read sets sqe->flags to 0, so we need to set the flags AFTER calling it.

if (g_use_iosqe_io_drain)

sqe->flags |= IOSQE_IO_DRAIN;

if (g_use_iosqe_io_link)

sqe->flags |= IOSQE_IO_LINK;

io_uring_sqe_set_data(sqe, my_data);

}

static void increment_buffer_index(int* head) // moves the producer or consumer head forward by one position

{

*head = (*head + 1) % g_numbufs; // wrap around when we reach the end of the ringbuf.

}

static void consumer_thread() // Conceptually, this resumes the consumer "thread".

{ // As this program is single-threaded, we can think of it as cooperative multitasking.

for (int i = 0; i < g_num_blocks_in_file; ++i){

while (g_ringbuf[consumer_head].state != AVAILABLE_FOR_CONSUMPTION) {} // busywait

// Consume the item.

// The producer has already checked that nbytes_expected is the same as the amount of bytes actually returned.

// If the read syscall returned something different to nbytes_expected then the program would have terminated with an error message.

// Therefore it is okay to assume here that nbytes_expected is the same as the amount of actual data in the buffer.

blake3_hasher_update(&g_hasher, g_ringbuf[consumer_head].buf_addr, g_ringbuf[consumer_head].nbytes_expected);

// We have finished consuming the item, so mark it as consumed and move the consumer head to point to the next cell in the ringbuffer.

update_cell_state(&g_ringbuf[consumer_head], ALREADY_CONSUMED);